The Many Morphs of Yoga in America

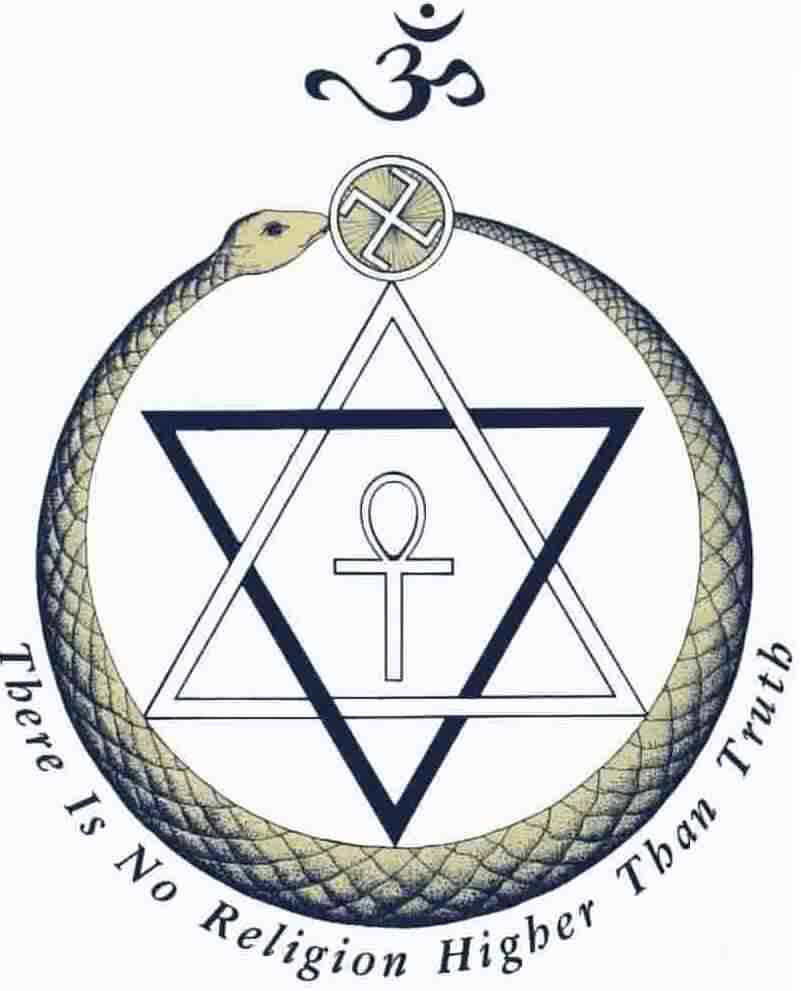

(image is the seal of the Theosophical Society)

The next couple of chapters in The Great OOM are a great overview of how many forms yoga took even when it originally hit America. With Pierre Bernard being put in jail and then on trial, all the many misconceptions of what yoga is, what Hinduism is, what the philosophies of yoga are and its purpose for practice all hit the headlines. Bernard was not alone in his American obsession with and intrigue of the practices and origins of yoga. Robert Love writes, “The transcendentalists and the Theosophists had begun their initial inquiries before Bernard was born. In fact, word of yoga arrived in the United States nearly a century before his birth – an idea in a cloud of ideas, both sacred and profane, from what was called ‘the Orient’: the vast, unknowable out there.”

I will not go into the theories and practices of transcendentalism and Theosophy here, nor the Vedanta of Vivekananda which is mentioned, but the history of those people, groups and movements are also quite interesting in and of themselves. Each of these movements read the ancient texts of yoga that are thousands of years old and came to strikingly different conclusions. Some viewed the body as dangerous and/or a burden and unnecessary, some viewed breath practices as dangerous and harmful, but the common denominator was at least the power and practices of the mind. In reality, the practice of yoga is ALL those things. It is the unity and understanding and discipline of ALL aspects of our being that is important. To truly be “unified”, we cannot neglect any of those pieces. That is why The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali list and name each of the “limbs” or pieces of the overall path, including covering the foundational moral and basic life principles to continue to come back to.

Where Bernard begins to distinguish himself is in his (and his teacher’s) emphasis on the Tantric tradition. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras may be viewed as more the ascetic and traditional path of yoga. Within the eight limbs, there is a balance of the “twin pillars” of Abhyasa (action) and Vairagya (renunciation), and a balance of the spiritual “SELF” (purusa) aligning with the outer Nature (Prakrti). On the other hand, the Tantric tradition embraces ALL aspects of life, body, experience, and Nature as spiritual and Divine. In Tantra, there is no need to reflect or consider our uses or abuses of any such things as everything is Divine. In my opinion, this is why Tantric philosophy has been controversial not just in its native India, but also here in the US. The ability for us to actually treat all of our experiences and indulgences as Divine without abusing them actually takes a lot of effort and discipline of the mind. Patanjali acknowledges the ancient human habits in the obstacles (Klesas) of Spiritual ignorance (Avidya), Ego attachment (Asmita), Pleasure seeking (Raga), pain averting (Dvesa), and attachment to life itself (Abhinivesa). If these are ignored, then you begin to see the problematic place of Tantra, but also why Tantra is so appealing as there is nothing in the end to have to “regulate” or “moderate” our behavior. Or even if there is a sense that all must be experienced, but “in moderation”, the WAYS and means to moderate those things are lost.

This is why we come to having even diligent practitioners of yoga abusing their powers, growing their egos, controlling others, or feeding their own egos more and more with whatever “levels of accomplishment” they perceive. Without the rest of the path of yoga that Patanjali acknowledges or without guidance from a teacher, the human mind DOES fall to the above obstacles as default. The interesting thing to me is that in writing, of course the thoughts of Tantriks are similar to that of Patanjali’s Yoga, just without all the warnings and recognition of the mental obstacles to overcome. As Robert Love recalls, in the views of Tantra, “the body is divine and thus the practice of hatha yoga became central to its sanctification. Tantrics believe that enlightenment is most profound when it involves the entire human body.” Similarly in Patanjali’s yoga, Asana (posture practice) is used to sanctify all areas of the body and are used as tools to focus the mind. Bernard also said “Body and soul are co-existent. One is but a manifestation of the other. The best way to perfect the soul is through the body and the senses…The first duty of every initiate is to purify his body and through his body improve his spirit.” What else are the practices of Yamas, Niyamas, Asana, Pranayama, and Pratyahara for other than all of the above? Again, the aim of all yoga is the same, but the detour that most Tantrics seem to take is to the abuses of such experiences, not keeping with the first foundational moral precepts that are so important in Patanjali’s Sutras and the path of yoga overall.

With all the abuses and controversies occurring not just with “The Great OOM”, but other grifters and charlatans around the country at the time, yoga went from being intriguing to being banned and feared. Even the Theosophists came to officially ban any discussion of yoga within its movement. By 1910, when Bernard finally got our of prison, “For any teacher of yoga – not to mention the profane hatha yoga that was Bernard’s calling- the public had nothing but contempt.”

Looking forward to now, I am fascinated by the cultural change in the overall acceptance of yoga, though the misconceptions and misunderstandings are still similar and rampant. As Love reminds us, “At its root, yoga is an experimental practice, its wisdom transmitted master to student, which requires actual masters, who were in short supply for most of our nation’s early history.” I would argue that “masters” are still in short supply even as teachers are a dime a dozen. Some see yoga as merely physical and discard the mental and spiritual foundation, some embrace just the spiritual and view the body as unnecessary or a burden. To pick and choose, to disregard, to morph the practice to something you “want” instead of something it truly is – a difficult discipline of mind and body to ultimately bring Nature and soul to balance and connection – is still a path away from the ultimate goal of yoga instead of towards it.